Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Next best thing

“The next best thing to having your stuff burned, if you’re ambivalent, is giving it to some guy who gives it to some lady who gives it to her daughters who keep it in an apartment full of cats, right?”

— From Elif Batuman’s article “Kafka’s Last Trial”, in the New York Times Magazine.

“The next best thing to having your stuff burned, if you’re ambivalent, is giving it to some guy who gives it to some lady who gives it to her daughters who keep it in an apartment full of cats, right?”

— From Elif Batuman’s article “Kafka’s Last Trial”, in the New York Times Magazine.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Meaning yes, message no

INTERVIEWER

When you say that sometimes you think your poetry is weird, what do you mean exactly?

ASHBERY

Every once in a while I will pick up a page and it has something, but what is it? It seems so unlike what poetry “as we know it” is. But at other moments I feel very much at home with it. It’s a question of a sudden feeling of unsureness at what I am doing, wondering why I am writing the way I am, and also not feeling the urge to write in another way.

INTERVIEWER

Is the issue of meaning or message something that is uppermost in your mind when you write?

ASHBERY

Meaning yes, but message no. I think my poems mean what they say, and whatever might be implicit within a particular passage, but there is no message, nothing I want to tell the world particularly except what I am thinking when I am writing.

— John Ashbery, interviewed by Peter A. Stitt in Paris Review, Winter 1983.

INTERVIEWER

When you say that sometimes you think your poetry is weird, what do you mean exactly?

ASHBERY

Every once in a while I will pick up a page and it has something, but what is it? It seems so unlike what poetry “as we know it” is. But at other moments I feel very much at home with it. It’s a question of a sudden feeling of unsureness at what I am doing, wondering why I am writing the way I am, and also not feeling the urge to write in another way.

INTERVIEWER

Is the issue of meaning or message something that is uppermost in your mind when you write?

ASHBERY

Meaning yes, but message no. I think my poems mean what they say, and whatever might be implicit within a particular passage, but there is no message, nothing I want to tell the world particularly except what I am thinking when I am writing.

— John Ashbery, interviewed by Peter A. Stitt in Paris Review, Winter 1983.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Flag Project, Ebony G. Patterson

Flag Project (work in progress), by Ebony G. Patterson. From Shot in Kingston: The Digital Scene, an exhibition of digital photo- and video-based work by younger Jamaican artists, part of Alice Yard’s 4x4 anniversary programme. Photograph by Rodell Warner.

Flag Project (work in progress), by Ebony G. Patterson. From Shot in Kingston: The Digital Scene, an exhibition of digital photo- and video-based work by younger Jamaican artists, part of Alice Yard’s 4x4 anniversary programme. Photograph by Rodell Warner.

Saturday, September 18, 2010

On “systemic indelibility”

Imagine that you are struck with a curious and rather outlandish thought that you don’t necessarily want to defend for the rest of your life but nonetheless feel compelled to share — if only to see how others react. You write an impassioned paragraph detailing your idea but pause before posting the entry online. Without an editor, you are the sole judge of the quality of your work, and you are aware that by hitting the “publish” button, you would be subjecting yourself to possibly harsh, often anonymous criticism. You must take into account the Internet’s systemic indelibility: that henceforth your entire intellectual stance could be defined by a single, possibly ill-conceived argument.

So you vacillate between killing the conversation before it begins or risking becoming “misrepresented and burned”.... Inevitably, this ends in some form of self-censorship. Not every form of online self-censorship is necessarily harmful — if people stopped documenting such things as the intimate details of their breakfast, society would hardly be worse off — but aside from oversharing, what will happen to plain sharing? Withholding inane tweets or provocative photos is one thing, but what will become of intelligent exchange and thoughtful conversation?

— Atossa Abrahamian on the epistemic consequences of a medium that “never forgives, and never forgets.”

Imagine that you are struck with a curious and rather outlandish thought that you don’t necessarily want to defend for the rest of your life but nonetheless feel compelled to share — if only to see how others react. You write an impassioned paragraph detailing your idea but pause before posting the entry online. Without an editor, you are the sole judge of the quality of your work, and you are aware that by hitting the “publish” button, you would be subjecting yourself to possibly harsh, often anonymous criticism. You must take into account the Internet’s systemic indelibility: that henceforth your entire intellectual stance could be defined by a single, possibly ill-conceived argument.

So you vacillate between killing the conversation before it begins or risking becoming “misrepresented and burned”.... Inevitably, this ends in some form of self-censorship. Not every form of online self-censorship is necessarily harmful — if people stopped documenting such things as the intimate details of their breakfast, society would hardly be worse off — but aside from oversharing, what will happen to plain sharing? Withholding inane tweets or provocative photos is one thing, but what will become of intelligent exchange and thoughtful conversation?

— Atossa Abrahamian on the epistemic consequences of a medium that “never forgives, and never forgets.”

Monday, September 06, 2010

“What’s valid?”

Boscoe Holder — artist, musician, dancer, raconteur, and a man who squeezed more pleasure out of life than most — died in 2007. He left behind several outrageous novels’ worth of stories and memories, and — more important — a large and crucial body of work, including hundreds of paintings and drawings in his studio.

Earlier this year, several of Holder’s portraits were included in an exhibition in Berlin co-curated by Peter Doig, the British artist who now lives in Trinidad, and the American writer Hilton Als. A few days ago, the New York Review of Books blog posted a conversation with Doig, Als, and the artist Angus Cook on “Discovering the Art of Boscoe Holder, Trinidadian Master”, accompanied by images of fourteen paintings.

I’m glad to think that Holder’s work may be reaching new and wider audiences, but reading this conversation left me bemused and bothered at statements such as:

Peter Doig: ...The drawback of Boscoe having lived and worked in Trinidad is that there is so little kept history — there’s almost no public archiving. It’s hard to know where all the Boscoe paintings are. The Caribbean being what it is, sadly, there’s not much interest in history. I mean, sometimes for good reason — people like to forget history. People like to knock down old colonial buildings.

Get rid of them, you know, who cares? Nothing is under preservation order. The weather destroys things. Photos disappear into the sunlight, books get eaten by all sorts of insects and stuff. I mean, everything there is kind of temporal, really. The forests and the jungle take over....

Hilton Als: I’ve been dreaming, literally, since last night, of the next show that I want to do with you. And we have to do it, and it’ll be called “After Rousseau.” And it’ll be Caribbean art, which no one ever shows, because they always think it’s, like, parasols and beach scenes. But it will be not just a show of paintings, but all sorts of things, like newspapers, all the shit that gets disappeared....

That’s what’s interesting to me, that it would be not just painting, but about the whole idea of reclaiming the past from the Caribbean, which is apt to destroy it.

I responded at the NYRB blog with this comment:

It’s pleasing to see a significant Trinidadian artist receiving critical attention and appreciation. (And I suppose the four small, unsigned Boscoe drawings I own are now worth a bit more than they were a few days ago.) But aspects of this conversation perturb me.

Words are slippery. They can mean different and unexpected things in different contexts. “Discovering”, in the Caribbean, is a heavily freighted word. Here in Trinidad and Tobago, we used to have a public holiday called Discovery Day, commemorating the occasion in 1498 when Columbus turned up off the south coast of Trinidad. We took Discovery Day off our calendar twenty-five years ago, but the notion of the Caribbean as a landscape ripe for discovery endures.

And I’m disturbed by statements like “there’s not much interest in history” and “everything there is kind of temporal, really”; and “the whole idea of reclaiming the past from the Caribbean, which is apt to destroy it.” Perhaps one ought not take casual conversational remarks too seriously, but these raise crucial and troubling questions about autonomy; about who has the right (or the resources) to claim or “reclaim” the past; and about what the late Trinidadian philosopher Lloyd Best called epistemic sovereignty.

This conversation also raises questions about what “history” means, and to whom, and who gets to write the definition. Someone who was born and has always lived in the Caribbean, like me, might think we are frequently over-burdened by a history that includes five centuries of colonial and neo-colonial exploitation. (I refer readers who don’t understand what I’m talking about to Derek Walcott’s poem “The Sea Is History”, as good a primer as any.)

I too worry about historic preservation in my country, the status of our archives, museums, and libraries, and the under-funding and -staffing of most public institutions charged with stewardship of our heritage. But I also worry that this state of affairs leaves the Caribbean vulnerable to external agents with their own concerns and priorities. I don’t espouse a crude cultural nationalism, or discount the often valuable work of foreign researchers, archivists, and collectors. And “outside” perspectives have their own validity. But there is a very long history of the Caribbean’s social and cultural complexities being represented by foreign voices. Caribbean artists, writers, thinkers, and citizens grapple with the challenge and the imperative to describe and define our own reality in and on our own terms.

Finally, I’m entirely puzzled by Hilton Als’s statement that “no one ever shows” Caribbean art “because they always think it’s, like, parasols and beach scenes.” Caribbean artists working in every conceivable medium — hardly just topographical painting — show in galleries and museums all over the world, even if they don’t always achieve the publicity or financial success of some of their North American and European contemporaries. In close proximity to Als in New York, and just in recent years, important shows of contemporary Caribbean artists have run at the Brooklyn Museum (Infinite Island, 2007-2008) and Real Art Ways in Hartford, Connecticut (Rockstone and Bootheel, 2009-2010). A retrospective on the Puerto Rican artist Rafael Ferrer just closed at El Museo del Barrio. El Museo is collaborating with the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Bronx Museum to organise a major tripartite Caribbean show to open in late 2011. These are only the first examples that come to mind.

As Peter Doig aptly says: “it makes you think, well, actually, what’s valid?”

Boscoe Holder — artist, musician, dancer, raconteur, and a man who squeezed more pleasure out of life than most — died in 2007. He left behind several outrageous novels’ worth of stories and memories, and — more important — a large and crucial body of work, including hundreds of paintings and drawings in his studio.

Earlier this year, several of Holder’s portraits were included in an exhibition in Berlin co-curated by Peter Doig, the British artist who now lives in Trinidad, and the American writer Hilton Als. A few days ago, the New York Review of Books blog posted a conversation with Doig, Als, and the artist Angus Cook on “Discovering the Art of Boscoe Holder, Trinidadian Master”, accompanied by images of fourteen paintings.

I’m glad to think that Holder’s work may be reaching new and wider audiences, but reading this conversation left me bemused and bothered at statements such as:

Peter Doig: ...The drawback of Boscoe having lived and worked in Trinidad is that there is so little kept history — there’s almost no public archiving. It’s hard to know where all the Boscoe paintings are. The Caribbean being what it is, sadly, there’s not much interest in history. I mean, sometimes for good reason — people like to forget history. People like to knock down old colonial buildings.

Get rid of them, you know, who cares? Nothing is under preservation order. The weather destroys things. Photos disappear into the sunlight, books get eaten by all sorts of insects and stuff. I mean, everything there is kind of temporal, really. The forests and the jungle take over....

Hilton Als: I’ve been dreaming, literally, since last night, of the next show that I want to do with you. And we have to do it, and it’ll be called “After Rousseau.” And it’ll be Caribbean art, which no one ever shows, because they always think it’s, like, parasols and beach scenes. But it will be not just a show of paintings, but all sorts of things, like newspapers, all the shit that gets disappeared....

That’s what’s interesting to me, that it would be not just painting, but about the whole idea of reclaiming the past from the Caribbean, which is apt to destroy it.

I responded at the NYRB blog with this comment:

•

It’s pleasing to see a significant Trinidadian artist receiving critical attention and appreciation. (And I suppose the four small, unsigned Boscoe drawings I own are now worth a bit more than they were a few days ago.) But aspects of this conversation perturb me.

Words are slippery. They can mean different and unexpected things in different contexts. “Discovering”, in the Caribbean, is a heavily freighted word. Here in Trinidad and Tobago, we used to have a public holiday called Discovery Day, commemorating the occasion in 1498 when Columbus turned up off the south coast of Trinidad. We took Discovery Day off our calendar twenty-five years ago, but the notion of the Caribbean as a landscape ripe for discovery endures.

And I’m disturbed by statements like “there’s not much interest in history” and “everything there is kind of temporal, really”; and “the whole idea of reclaiming the past from the Caribbean, which is apt to destroy it.” Perhaps one ought not take casual conversational remarks too seriously, but these raise crucial and troubling questions about autonomy; about who has the right (or the resources) to claim or “reclaim” the past; and about what the late Trinidadian philosopher Lloyd Best called epistemic sovereignty.

This conversation also raises questions about what “history” means, and to whom, and who gets to write the definition. Someone who was born and has always lived in the Caribbean, like me, might think we are frequently over-burdened by a history that includes five centuries of colonial and neo-colonial exploitation. (I refer readers who don’t understand what I’m talking about to Derek Walcott’s poem “The Sea Is History”, as good a primer as any.)

I too worry about historic preservation in my country, the status of our archives, museums, and libraries, and the under-funding and -staffing of most public institutions charged with stewardship of our heritage. But I also worry that this state of affairs leaves the Caribbean vulnerable to external agents with their own concerns and priorities. I don’t espouse a crude cultural nationalism, or discount the often valuable work of foreign researchers, archivists, and collectors. And “outside” perspectives have their own validity. But there is a very long history of the Caribbean’s social and cultural complexities being represented by foreign voices. Caribbean artists, writers, thinkers, and citizens grapple with the challenge and the imperative to describe and define our own reality in and on our own terms.

Finally, I’m entirely puzzled by Hilton Als’s statement that “no one ever shows” Caribbean art “because they always think it’s, like, parasols and beach scenes.” Caribbean artists working in every conceivable medium — hardly just topographical painting — show in galleries and museums all over the world, even if they don’t always achieve the publicity or financial success of some of their North American and European contemporaries. In close proximity to Als in New York, and just in recent years, important shows of contemporary Caribbean artists have run at the Brooklyn Museum (Infinite Island, 2007-2008) and Real Art Ways in Hartford, Connecticut (Rockstone and Bootheel, 2009-2010). A retrospective on the Puerto Rican artist Rafael Ferrer just closed at El Museo del Barrio. El Museo is collaborating with the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Bronx Museum to organise a major tripartite Caribbean show to open in late 2011. These are only the first examples that come to mind.

As Peter Doig aptly says: “it makes you think, well, actually, what’s valid?”

Sunday, September 05, 2010

The world’s strange bounty, no. 4

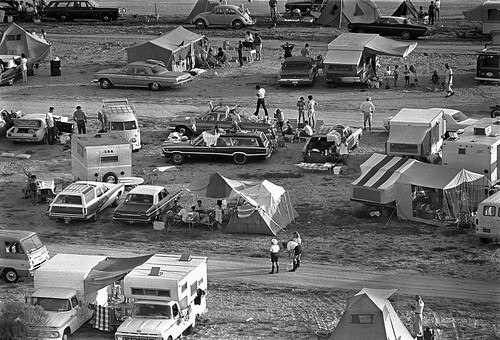

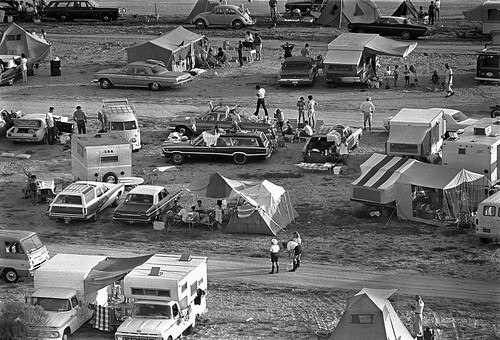

Spectators of the Apollo 11 launch on a beach near the NASA Kennedy Space Centre, 16 July, 1969. Copyright-free image posted at Flickr by NASA.

Spectators of the Apollo 11 launch on a beach near the NASA Kennedy Space Centre, 16 July, 1969. Copyright-free image posted at Flickr by NASA.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)